Song of Albatross, of freedom, of aspiration, of prayer, of a fledging bird that is wandering, hovering and waiting..."that made the bleeze to blow"

10/31/2008

远来的和尚

不过随阴雨天气一同到来的也不尽是令人扫兴的消息,比如说“高僧”Michael Tomasello就千里迢迢从东边赶来讲经。一同助阵的还有Joan Silk, Carol Dweck, Brian Skyrms, Elizabeth Spelke等一干高手,台下听众的重量级也毫不逊色,比如说今天讨论会上坐在我右手边的就是Robert Seyfarth(此人一进屋我就觉得面熟,直到散了会才想起来是他)。三天的报告会最大特点是多样性,五湖四海、三教九流齐聚,做心理学的、人类学的、生物学的、经济学的、哲学的、政治学的……坐在我左边的居然是英语系的教授!

会议组成虽然复杂,话题倒是十分统一,只是思维方式和分析角度各不相同,争论起来也甚是热闹。核心话题在于人类的社会合作倾向从何而来?笼而统之的答案当然是进化(神创论者基本不会来参加这样“荒谬”的会议),但是更具体的细节就没人能说清楚了,当下主要的争议在于ontogenesis和phelogenesis两条路径的比重究竟各占几成。这一分歧与语言起源的问题基本一致,一派讲天赋论(类比于Chomsky的universal grammar),另一派推习得论(类比于Skinner的operant)。新近的实验性研究结果一般都暗示介于两者之间的每种状态,不过人文学者仍多倾向于前者。人与猩猩在行为上的差别是显而易见的,问题在于这种差别究竟是量的差别还是质的差别,以及造成差别的关键到底在哪里。由于学科传统不同,大家对同一现象的解读方式和标准各不相同,比较倒是好事,美中不足是平衡有一点儿比例失调,基本上是Tomasello的传统心理学行为研究思路所主导,如果能有两个做神经科学的人进来提供一点新的发现和思路来平衡一下就更好了。

会后有人问我感想如何,我说:听Tomasello的报告很是兴奋,不过话说回来,如果我当初去了马普,Joan Roughgarden从美国飞过去做报告,我也会一样兴奋的。总之是远道的和尚会念经。

10/24/2008

Cold Shoulder and Warm heart: More than Metaphors

Chen-Bo Zhong, G.J.L., 2008. Cold and Lonely: Does Social Exclusion Literally Feel Cold? Psychological Science, 19:838-842.

Metaphors such as icy stare depict social exclusion using cold-related concepts; they are not to be taken literally and certainly do not imply reduced temperature. Two experiments, however, revealed that social exclusion literally feels cold. Experiment 1 found that participants who recalled a social exclusion experience gave lower estimates of room temperature than did participants who recalled an inclusion experience. In Experiment 2, social exclusion was directly induced through an on-line virtual interaction, and participants who were excluded reported greater desire for warm food and drink than did participants who were included. These findings are consistent with the embodied view of cognition and support the notion that social perception involves physical and perceptual content. The psychological experience of coldness not only aids understanding of social interaction, but also is an integral part of the experience of social exclusion.

Williams, L.E. and Bargh, J.A., 2008. Experiencing Physical Warmth Promotes Interpersonal Warmth. Science, 322:606-607.

"Warmth" is the most powerful personality trait in social judgment, and attachment theorists have stressed the importance of warm physical contact with caregivers during infancy for healthy relationships in adulthood. Intriguingly, recent research in humans points to the involvement of the insula in the processing of both physical temperature and interpersonal warmth (trust) information. Accordingly, we hypothesized that experiences of physical warmth (or coldness) would increase feelings of interpersonal warmth (or coldness), without the person's awareness of this influence. In study 1, participants who briefly held a cup of hot (versus iced) coffee judged a target person as having a "warmer" personality (generous, caring); in study 2, participants holding a hot (versus cold) therapeutic pad were more likely to choose a gift for a friend instead of for themselves.

Myth break up

Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve chairman, with John Snow, former Secretary of the Treasury, at a hearing on Capitol Hill on Thursday.

Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve chairman, with John Snow, former Secretary of the Treasury, at a hearing on Capitol Hill on Thursday."Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief."

“Yes, I’ve found a flaw. I don’t know how significant or permanent it is. But I’ve been very distressed by that fact.”“Were you wrong?” Mr. Waxman asked.

“Partially,” the former Fed chairman reluctantly answered.

10/12/2008

The Misused Impact Factor

The Misused Impact Factor -- Simons 322 (5899): 165 -- Science

Research papers from all over the world are published in thousands of Science journals every year. The quality of these papers clearly has to be evaluated, not only to determine their accuracy and contribution to fields of research, but also to help make informed decisions about rewarding scientists with funding and appointments to research positions. One measure often used to determine the quality of a paper is the so-called "impact factor" of the journal in which it was published. This citation-based metric is meant to rank scientific journals, but there have been numerous criticisms over the years of its use as a measure of the quality of individual research papers. Still, this misuse persists. Why?The annual release of newly calculated impact factors has become a big event. Each year, Thomson Reuters extracts the references from more than 9000 journals and calculates the impact factor for each journal by taking the number of citations to articles published by the journal in the previous 2 years and dividing this by the number of articles published by the journal during those same years. The top-ranked journals in biology, for example, have impact factors of 35 to 40 citations per article. Publishers and editors celebrate any increase, whereas a decrease can send them into a huddle to figure out ways to boost their ranking.

This algorithm is not a simple measure of quality, and a major criticism is that the calculation can be manipulated by journals. For example, review articles are more frequently cited than primary research papers, so reviews increase a journal's impact factor. In many journals, the number of reviews has therefore increased dramatically, and in new trendy areas, the number of reviews sometimes approaches that of primary research papers in the field. Many journals now publish commentary-type articles, which are also counted in the numerator. Amazingly, the calculation also includes citations to retracted papers, not to mention articles containing falsified data (not yet retracted) that continue to be cited. The denominator, on the other hand, includes only primary research papers and reviews.

CREDIT: JUPITERIMAGESWhy does impact factor matter so much to the scientific community, further inflating its importance? Unfortunately, these numbers are increasingly used to assess individual papers, scientists, and institutions. Thus, governments are using bibliometrics based on journal impact factors to rank universities and research institutions. Hiring, faculty-promoting, and grant-awarding committees can use a journal's impact factor as a convenient shortcut to rate a paper without reading it. Such practices compel scientists to submit their papers to journals at the top of the impact factor ladder, circulating progressively through journals further down the rungs when they are rejected. This not only wastes time for editors and those who peer-review the papers, but it is discouraging for scientists, regardless of the stage of their career.

Fortunately, some new practices are being attempted. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute is now innovating their evaluating practices by considering only a subset of publications chosen by a scientist for the review board to evaluate carefully. More institutions should determine quality in this manner.

At the same time, some publishers are exploring new practices. For instance, PLoS One, one of the journals published by the Public Library of Science, evaluates papers only for technical accuracy and not subjectively for their potential impact on a field. The European Molecular Biology Organization is also rethinking its publication activities, with the goal of providing a means to publish peer-reviewed scientific data without the demotivating practices that scientists often encounter today.

There are no numerical shortcuts for evaluating research quality. What counts is the quality of a scientist's work wherever it is published. That quality is ultimately judged by scientists, raising the issue of the process by which scientists review each others' research. However, unless publishers, scientists, and institutions make serious efforts to change how the impact of each individual scientist's work is determined, the scientific community will be doomed to live by the numerically driven motto, "survival by your impact factors."

10.1126/science.1165316

Kai Simons is president of the European Life Scientist Organization and is at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany.

10/07/2008

Old wine in new bottles: Two pieces about 'Science'

By James Williams

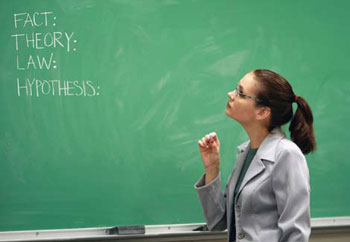

What makes me feel embarrassed is that I found difficult to make the definitions by myself.Here are some of the data from the 74 graduates that I've surveyed to date:

• 76% equated a fact with 'truth' and 'proven'

• 23% defined a theory as 'unproven ideas' with less than half (47%) recognizing a theory as a well evidenced exposition of a natural phenomenon

• 34% defined a law as a rule not to be broken, and forty-one percent defined it as an idea that science fully supports.

The Scientist : Why the Philosophy of Science Matters [2008-10-01]

By Richard Gallagher

You might expect that newly minted science graduatesᅠ-ᅠwho presumably think of themselves as scientists, and who I'd thought of as scientistsᅠ-ᅠwould have a well-developed sense of what science is. So it's pretty shocking to discover that a large proportion of them don't have a clue.Please pay attention to the comment following the article on the site.

Capitalism in trouble

We don't just need to recapitalize the banks. We need to reconceptualize capitalism.

By Jacob Weisberg

Posted Saturday, Oct. 4, 2008, at 7:51 AM ET At the beginning of the century, when the United States briefly contemplated the prospect of paying off its national debt, Alan Greenspan raised an unexpected concern. A government surplus would end up being invested in private assets, which would violate free-market principle and could deliver socialism through the back door.

Greenspan smothered that dangerous surplus in its crib by endorsing the Bush tax cuts, but his benign view of derivatives and his nonchalance about the unregulated "shadow banking system" helped bring about the outcome he feared anyhow. Authorizing the Treasury Department to take stakes in financial firms is merely the Paulson plan's most dramatic departure from textbook capitalism. The legislation—which the Senate had enough sense of irony to attach to a mental health bill—implicitly recognizes that major financial institutions have become too interwoven with the global economy to be allowed to fail.

What should we call the economic model emerging from this crisis of capitalism? Despite the collectivization of losses and risk, it doesn't qualify as even reluctant socialism. Government ownership of private assets is being presented as a last-ditch expedient, not a policy goal. Yet it's inaccurate to describe our economy, either pre- or post-Paulson, as simply laissez faire. A system in which government must frequently intervene to protect the world from the results of private financial misjudgment is modified capitalism—part invisible hand, part helping hand. This leaves us with a pressing problem of both conceptualization and nomenclature.